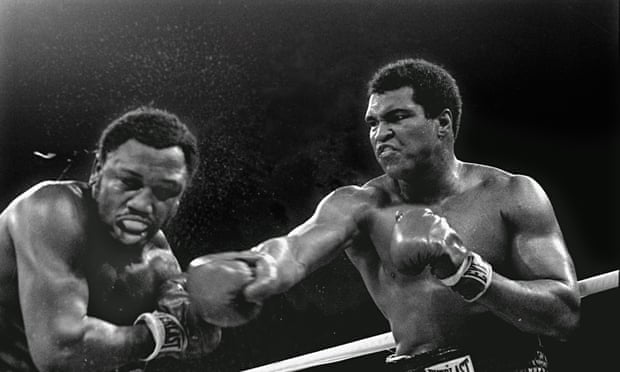

For the purposes of commerce, showbusiness and Don King’s love of mangled rhymes, it was called the Thrilla In Manila. In reality, the third, final and quite frightening fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, on this day 40 years ago, ought to be remembered as The Fight Too Far.

Both came to the battle weary, aged and struggling to contain self-delusion. They left damaged and irreparably bitter. Ali won, famously, when Frazier’s kind and wise trainer, Eddie Futch, refused to let him go out for the 15th round, exhausted and near-blind.

But the contest lingered verbally way after the bell, all the way to Joe’s grave. This most noble of fighters struggled properly to forgive Ali for some of the most hurtful insults ever hurled in the name of sporting hype, and convinced himself in repeated assertions to anyone who’d listen that he could have survived one more round.

In that respect, Frazier did win. He won respect for his courage and sympathy for his plight as Ali’s plaything, the straight man in a joke he never understood. Joe sweated blood and dignity in equal measure.

This was the pivotal event of their existence. All their history was poured into the 42 minutes in which they tried to bury each other for good. The fight was the closest to sanctioned manslaughter boxing had allowed since 187lb Jack Dempsey demolished the 6ft 6in champion Jess Willard in three rounds on 4 July, 1919.

For those who missed the latter part of the 20th century, a brief recap: Frazier knocked down and beat Ali at Madison Square Garden over 15 tremendous rounds in 1971, with more celebrities ringside than your average Frank Sinatra concert. Indeed, Frank got a gig taking photographs for Life magazine so he could see the fight – and Diana Ross was ejected from the press seats when she tried to sneak in for a better view.

Three years later, Ali overcame Frazier in a much lesser contest, with no title at stake, to bring it all square. And then, on 1 October, 1975, in the Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City, they collided like dinosaurs one more time.

Ali arrived rehabbed and as loud as ever, having destroyed Frazier’s conqueror, George Foreman, in Zaire a year earlier. After seven years in the shadows, he was the king again. It was hard to believe. And Frazier was no believer.

There had always been an edge to their relationship. Frazier resented the fact Ali never fully appreciated his efforts to help him when he was ostracised as a conscientious objector at the height of the Vietnam War, when the world did not adore Ali as they later would, when he was untouchable, a religious zealot regarded as morally and politically dangerous, and of no great worth as a saleable fighter any more.

But Ali proved them all wrong with his gloves, and Frazier came to Manila secretly grateful for that. If he could beat The Greatest two out of three, surely he would be The Greatest.

Before a blow had landed, however, Ali slipped up badly. As his biographer Thomas Hauser recalls: “He labelled Joe a gorilla, with all the ugly racial stereotyping that involves. There are things that Ali said to Joe I’m sure he forgot 10 minutes later, but they cut very deep.”

One of the possible reasons Ali was out of control at that time is that his personal life was in disarray and none of the sycophants around him could rein him in. He was married to his second wife, Belinda, but also to self-indulgence. The couple rowed angrily in their hotel room. Soon, he would leave Belinda for Veronica Porsche.

Joe, quietly and with all the innocence of a child, responded at the time: “I can’t see anyway I look like any old gorilla. We’re supposed to be from the same ancestors. When a guy speak to another man like that, he’s not quite sure of himself.”

This was no isolated onslaught by Ali. For several years he had mocked Frazier, his defence being that is what he did to every opponent, from Sonny Liston to Floyd Paterson to Foreman. Joe wasn’t buying it. And he would reply the only way he knew how.

They both trained to the limits of their reduced capacity. As Hauser correctly observes: “Neither guy was as good as they had once been, but their downward curves intersected at just the right point. It was an historic battle.”

The tin roof and TV lights turned the arena into a steam cooker. As the rounds passed, only their conditioning and heart kept them going. Ali dominated early, then Frazier, then Ali, before these fast-aging throwbacks entered into a mutual destruction pact, ignoring all consequences, pounding each other with arms steadily drained of sharpness but laden still with bad intentions.

Ali looked like knocking Frazier out in the 13th round, again in the 14th.

When they hit the stools after those closing three minutes, Futch at first begged Frazier to quit. His right eye was shut, his left not working perfectly anyhow, so he was effectively near blind. “No, no, no, come on Eddie!” Joe replied. Eddie insisted. It was done.

And then a twist – as Frazier recalls: “What we didn’t know was that Muhammad wasn’t gonna come out.”

That has been the enduring tale about the finish of the fight – but Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer, protested in an ITV documentary years later: “Believe me, it never happened. I’m the only guy talking in the corner, and Muhammad never talked back at me. I would shut him up. No, not a word about quitting. Muhammad didn’t know what quit was.”

And he didn’t. But we’ll still never know the indisputable truth. Perhaps that was the night he couldn’t give any more. He gave enough, whatever the result – more than enough. Both of them did, more than anyone had a right to demand, or pay for. It was an awesome exhibition of all the best and worst of prizefighting.

Afterwards, according to boxing ritual, respect flowed. “He’s greater than I thought he was,” Ali said at the press conference. Frazier commented: “I thought the man put up a good fight. I guess we’ll be seeing each other some time again. I hope anyway.”

They would not meet again. They would eventually slide into decline, leaving the fight game within a week of each other in 1981. And they would be remembered above all their other mutual deeds for this one, The Fight Too Far.

No comments:

Post a Comment